To begin any piece on photography with a remark about the medium’s relation to time might appear a rather facetious strategy, but in the case of David Farrell’s Before, During, After… Almost, questions of time – and indeed, of timeliness – are in fact paramount. The book, which also functions as a catalogue for an exhibition of the same name held in the RHA, Dublin, brings together several bodies of work made over a number of years, encompassing the breadth of Farrell’s practice as a photographer, shifting in style and emphasis, but in this case all centred around the notion of Irishness, considered in various, if rarely definitive ways. The range of the work, as well as the span of time it encompasses, is foregrounded by the two images that can be found inside the front and back covers, opening with a grainy, black and white view of the Irish tricolour hanging slack over the ornate façade of the GPO[i] and closing with a crisp, flash-lit colour image of a hoarding on which someone has written the word “Truth,” though a later hand has altered this slogan so that the word “trick” appears intertwined between the letters (how easily the switch can be made). These images, produced nearly two decades apart, contain the essence of Farrell’s stylistic evolution as a photographer, which is at the same time in contrast to a remarkably consistent probing of the social and cultural fault-lines that define his native Ireland.

The timeliness of the book, given the largely unreflective attitude that has marked the 1916 centenary, means that it has the potential to be a significant corrective statement, considering the psychologically scarred and politically riven landscape that Farrell depicts, a “failed Republic,” as he calls it in an accompanying interview. However, this ‘failure’ is far more ambiguous than mere political reality; it is certainly not the failure of a putative Republican ideal, mourning for what might (supposedly) have been. In fact, what the pictures detail is essentially the failure of that damagingly pious conception of the Republic on its own terms, and a working through of the extended consequences of this failure, which continue to define the nature of the state. The book is also an excavation of Farrell’s own personal archive, an archaeology of work seen, such as Innocent Landscapes, perhaps his best known project, and unseen, such as the series Before, During, After, a previously unpublished work that considers the declining landscape of Irish Catholicism in the 1990s. This series is actually the nucleus of the book; its unique intensity, a blend of rigorous observation and metaphorical weightiness, would stay with Farrell through stylistic changes and developing themes. Aided by strong design from Peter Maybury, mixing recent pictures with ‘archival’ extractions, he builds on that early recognition of how forces implicit in the conception of the Irish Republic would shape – and deform – the present.

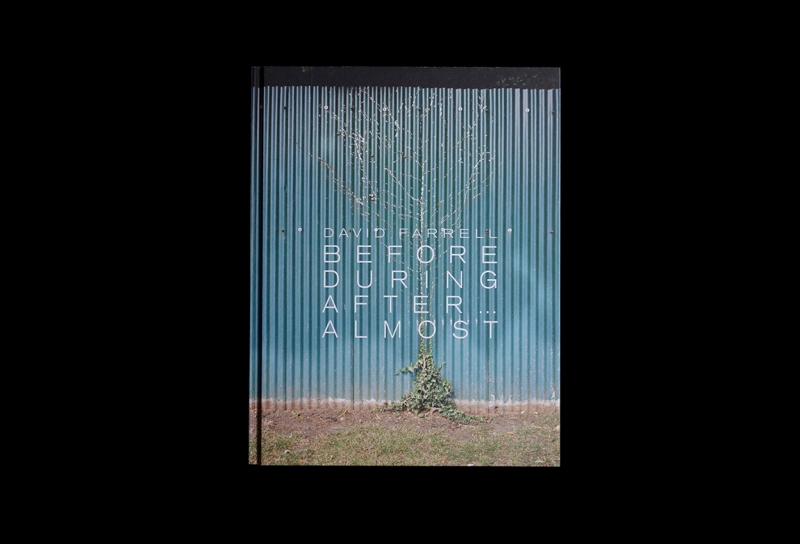

What matters, however, is not simply accounting for past events, but the determination to articulate an understanding of how these historical moments continue to echo for us now; it is, in short, the recognition of the past in the present, an act of synthesis that depends here, both conceptually and to a certain extent aesthetically, on the distance between Farrell’s earlier and current work, given a sufficient accumulation of time to see how patterns form, how subterranean influences play out. The mere work of excavation is not – and cannot be – enough. What the integration of these different bodies of work achieves is a narrative density that can make visible the patterns, the echoes, that are the driving forces of contemporary Irish life, the same fateful gestures being played out again and again. Something of this inevitability can be seen in the resonant cover image, which shows where the growth of ivy up a (green) corrugated iron barrier has been cut back, leaving a cross-like pattern, the ghost of its own former vitality. But it is obvious that the plant will try to grow back in the same place, tracing once more what has been lost. That no easy conclusion can be drawn from this is typical of Farrell’s approach; it initially might be read as a somewhat optimistic evocation of resilience and yet there is also something almost doomed in the sense of endlessly replaying the same fate.

Excavation is, of course, also a prominent subject in Farrell’s work, with the continuing process of photographing the sites of searches for the remains of those people who ‘disappeared’ as a result of sectarian tensions in Northern Ireland. In these instances, we can see how the bucolic Irish landscape – picture-perfect, as it were – is being torn apart in order to locate the victims of senseless violence; that it is, in a way, necessary to destroy the landscape (as image) in order to redeem, so far as might be possible, the brutal imposition of history on individual lives. The pictures of the later searches demonstrate a shift towards thinking more explicitly about time, marked both by the changes in the landscape, where nature smooths over the incursion of the searches, hiding their traces, just as the victims were hidden, and also in the length of time that the searches themselves have been taking place, as though they were a physical expiation of our collective guilt, the work of memory and of mourning. This labour is necessarily unfinished, because we are unable to confront the causes of such violence, which still remain under the surface. Enough of these pictures are threaded throughout the book to remind us that ideological conflicts have tangible consequences, though its structure is such that their exact implications are not immediately apparent, they are simply folded into the narrative as one persistent legacy of our national ‘heritage’ among others.

This idea of excavation is foregrounded in another sense by a picture in the opening sequence of the book, which shows the foundation work for one of the many new developments that characterised the so-called Celtic Tiger years[ii]. Rows of concrete support pillars have been placed in a cleared site, which also seems to be a palimpsest of previous constructions, visible as exposed layers within the new excavation. Our past is always implicit in the present, to the extent the world we inhabit is – sometimes literally – built over it, and indeed, from it. The construction boom of those years is another key theme here; weird pastel-coloured confections that have sprung up on postage stamp-sized plots are typical of this new landscape, which, however much it might have aspired to a notion of historical continuity (spurious ‘glens’ and ‘vales’ abound), actually speaks to a profound sense of alienation, a place where people live side-by-side, but by no means live together. Often the developments are imposed haphazardly on the landscape, fated never to be occupied or even finished. An air of futility hangs over places that should have been – or were sold as being – new, thriving neighbourhoods and now stand as if abandoned. What those years – and the reactions to the subsequent crisis they provoked – seem to represent, in Farrell’s view at least, is another chapter in the failure to create and to sustain a meaningful form of national community, as opposed to one that is bought cheap and to turn a profit, or equally, one that is sustained by an oppressive culture of pious observance.

That the core work of the present collection is taken from the previously unpublished work Before, During, After has already been noted. This project was an examination of the Catholicism’s decline in Ireland, though the very idea of ‘decline’ would surprise many even still, so identified is Ireland with the burden of faith. What these pictures describe, among other things, is the stage of lingering attachment that inevitably accompanies the shifting of any social force; as the stability it provided begins to erode, the more extravagant the devotion of the dwindling faithful becomes. For everyone else, ritual is reduced to mere habit – or, more accurately, is revealed as habit. But the Church was (or presumed itself to be) the moral and emotional centre of Irish life, so that the tangible decline of its influence left a void that there was no way of filling, a situation made worse by the fact that its influence was later shown to have been so fundamentally corrosive. The sense of the Church in decline is powerfully illustrated by a number of images here, though perhaps none more so than the portrait of the almost faceless priest at a pro-life rally clad in a rather tattered black overcoat that, given its poor fit, seems in fact to have once belonged to someone else; much the same might be said of contemporary Ireland’s relation to the faith that once defined it.

Obsessive attachment to Catholicism substitutes for the supposedly botched Republic (religious and political observance in Ireland have ever been twinned) and then, in the void created by the collapse of the Church’s spurious authority, comes the lure of being a nation on the up, looking confidentially to a borrowed future, typified by the images of perfect homes promised by the advertising for the seemingly endless spate of new residential developments from the last fifteen years or so. In Ireland, forever a nation of emigrants, of the dispossessed, the notion of ‘home’ is still an incredibly potent one. But in Farrell’s view these developments are all almost perfect in their sheer emptiness, a dream often literally built on sand. Of course it is fanciful to imagine that the boom of the Celtic Tiger years was anything besides simple greed fuelled by a lending bubble and exacerbated by international forces far beyond the scope of such a small country. At the same time, history does tend to imply a distinct continuity, linking where we have been to where we are, and so, in that sense, there is something undeniably suggestive in the sight of three concrete pillars rising like crosses on Calvary at the edge of yet another infamous ‘ghost’ estate – haunted, in every sense.

It is the sequencing that develops the sustained connection between each individual series, drawing out such resonances, so that the book is, at least, the sum of its parts – and not only that. It also marks Farrell’s dogged engagement with the most pressing questions of contemporary Irish life; questions that, even if largely without answers, might be seen to define the changing nature of Irishness itself, as a fraught and at times highly volatile set of conditions. This unsettled quality is echoed by the design also, which in many instances tends to place the image to the far margin of the page. This has the dual effect of driving the narrative on, while also suggesting that the story is fundamentally unfinished, leading somewhere else. The use of repetition is also an important strategy here. It serves to reinforce the idea of historical circularity, playing out the same situation in different guises, with the same outcomes. Especially striking in this respect is the repeated image of a sunlit grove of trees that contains at its centre a knot of darkness, functioning like the reverse of the popular idiom; it is, in fact, the tunnel at the end of the light, or at least the looming presence of something sinister and irresistible in an archetypally lush, green landscape. Growth is always around – and perhaps, in spite of – the darkness at its core. In instances like this, Farrell’s specifically Irish subject-matter does begin to take on a wider resonance, though it remains grounded in the consideration of our national identity as a set of received ideas – and images.

There are, of course, other themes that run through the book, though these are, for the most part, rather less prominent than the main issues that Farrell has considered. Worth mentioning, however, is the role of Irish soldiers in the British Army during the First World War. This is addressed by just two pictures, both landscapes, that show the reclaimed battlefields of France, their horrors now only a memory, if even that. These pictures are also a work of reclamation, employing the same strategies that defined his Innocent Landscapes project, though admittedly of nothing like the same duration or scope. Irish soldiers who fought for the British Army in the First World War endured a legacy of shame and official neglect in the nationalist context of the new Irish state so that their sacrifice could not, until very recently, be recognised as it was elsewhere. In a way, this blind spot of national memory resembles the plight of ‘the disappeared’ as forgotten victims of history, so it makes sense to connect them, however subtly, in the narrative. The battlefields of France never seem to be been a fully-fledged body of work for Farrell, but as this book also represents an excavation of his own archive, it makes thematic sense that this material should be included here, even if it was something he didn’t ultimately pursue.

Coming to the end of Before, During, After… Almost, what surprises is the extent to which this ostensibly retrospective collection of different projects can function as something unified and coherent. Less unexpected, despite the fact that it was at least partly occasioned by the official flag-waving of the 1916 centenary, is the decidedly pointed relationship the work has to Irish history, even if it is ultimately sympathetic to what might be seen as the existential undercurrent in the persistence of these collective failures. In light of Farrell’s preference for revisiting subjects (and of the element of time in this book), repeated images of the Republican monument in St. Paul’s Cemetery, Glasnevin are especially telling. The first, from the early 90s, reveals a brutal concrete monolith, the builders of which saw fit to leave out a crucial line (“Enough to know…”) from the poem by W.B. Yeats that adorns it, while a subsequent image implies – rather than directly shows – the updated monument.[iii] This is the process of historical revision in action, then; but what, if anything, can be “enough” here? The knowledge that Yeats suggests is not mere justification, but something far more ambiguous. Its rejection would mean a culturally, politically and – for want of a better word – spiritually immature society, incapable of facing its own demons, held captive to the past and doomed to repeat it. The enduring legacy of this stunted growth is exactly what these pictures show.

Our national identity is, of course, a product of this same history; the forces that have defined Irish life are manifested there, for better or worse, and the terms of that identity shape not only how others see us, but also how we see ourselves. It is the limitations of this identity that David Farrell is chasing in this work, whether they are manifested in specific instances or simply in the textures of the everyday. So when he speaks of a “failed” Republic, both the causes of that failure and its effects are reflected in how unstable this identity has proven itself to be, torn between an unrealised – indeed, impossible to realise – version of the past, the legacy of seemingly immovable institutions and, more recently still, a vision of the future that was nothing so much as the fever dream of speculators and craven profiteers. Farrell locates the burden of this history and the assumptions we have about it, firmly in the here and now, where its repercussions must necessarily continue to be felt. Mining a productive space between description and metaphor, his pictures are definitely ‘about’ the world we live in, its social and historical conditions, but they are not confined to it either. What this work touches on, in fact, are the often intangible reaches of our own history, that, even as we continue living it, seem to elude us.

David Farrell, Before, During, After… Almost, published by the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA), Dublin. The book is available from their website. All images courtesy of the artist – www.davidfarrell.org

[i] The General Post Office on Dublin’s O’Connell street was one of the main sites occupied by the rebels in 1916. It is also where Patrick Pearse declared the existence of the fledgling Irish Republic to a handful of bemused and largely uncomprehending passers-by.

[ii] A much over-used term, admittedly. But for the sake of argument let’s say the Celtic Tiger period proper runs from a slow start in the early 90s up to around 2001 when growth began to falter, only to be sustained thereafter by the combined effects of a lending and property bubble, leading to the inevitable crash in 2008.

[iii] The (corrected) quotation now reads: “We know their dream; Enough to know they dreamed and are dead”. The poem is Easter 1916. Readers interested in Yeats’ connection to nationalism should look to R.F Foster’s excellent two-volume biography.

Hi Darren – that’s a magisterial piece of writing on a very fine book.

When I asked him, David Farrell said he had tried to include what I think is one of his finest images – a photo of the empty Board room of the Central Bank hovering as a reflection over the city at night . Its as concise and as eloquent a comment on the madness of international finance capital as ever there could be. Reading your piece makes me think even more that this picture ‘should’ have worked within these covers . So why didn’t it? Does the book’s overall aesthetic (its mix of styles that all still hang together) preclude the pointed brashness of that Central Bank series?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! The book really is a considerable achievement – I do know the picture you mean and there certainly is a case to be made that it could/ should have been included. but, equally, it seems to me that the crash – though it obviously had its roots in the banking system – was most visible here in terms of its effect on property, always a very loaded subject for Irish people, and the complexity of that relationship is, I think, well represented by the book as it is. David might have a different take, but that’s mine.

LikeLike